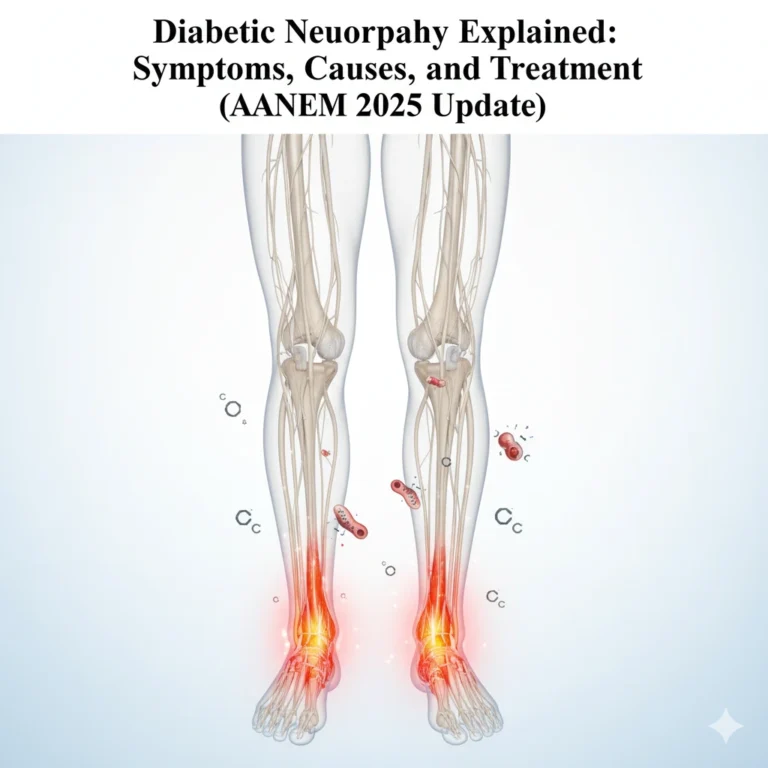

Introduction: Why Diabetic Neuropathy Matters

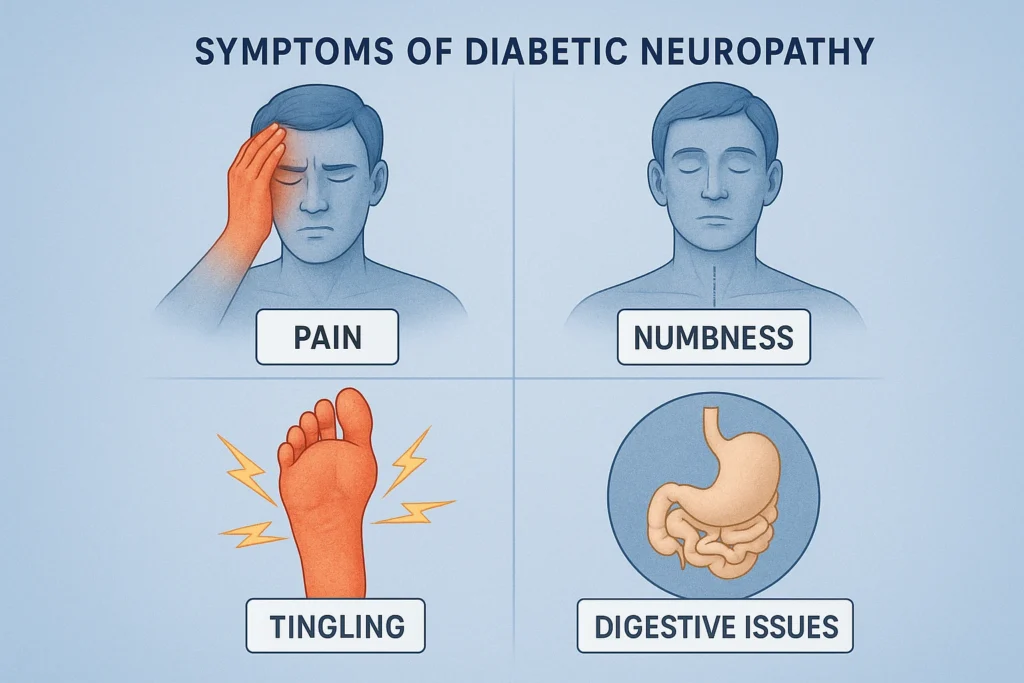

Diabetic neuropathy is one of the most frequent complications of diabetes, affecting nearly half of all people with diabetes during their lifetime. It can cause pain, numbness, muscle weakness, and autonomic dysfunction — symptoms that severely affect mobility, sleep, and quality of life.

As global diabetes rates continue to rise, understanding diabetic neuropathy has never been more critical. This article summarizes the latest insights from the 2025 AANEM Monograph, including recent updates on mechanisms, diagnosis, and modern management strategies.

What Is Diabetic Neuropathy?

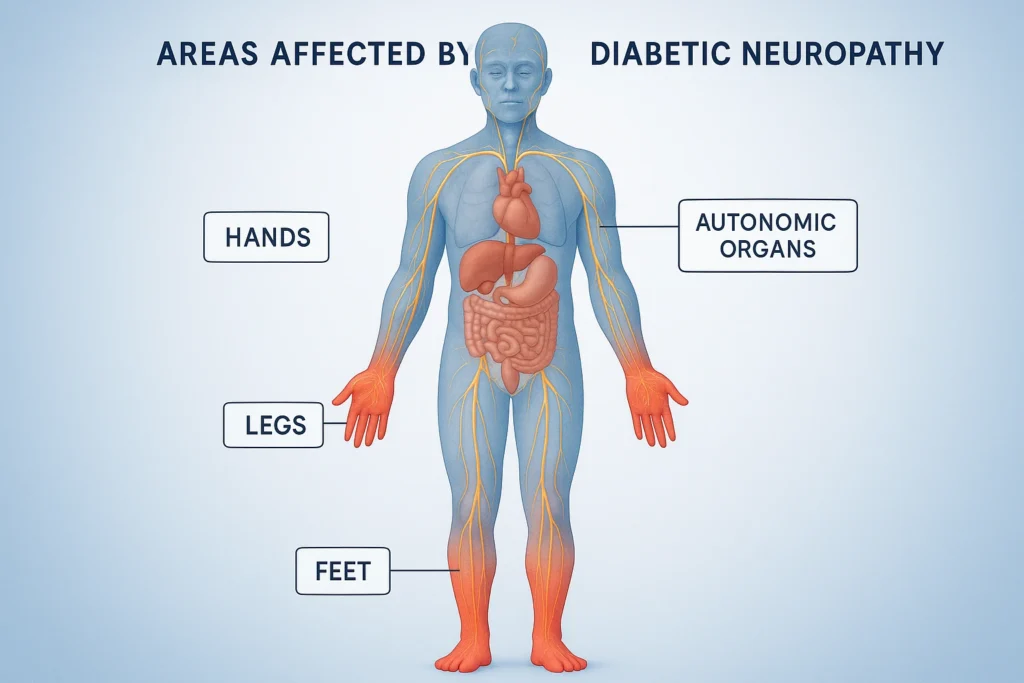

Diabetic neuropathy refers to nerve damage caused by chronic high blood glucose levels and metabolic stress. It most commonly affects the peripheral nerves — particularly those in the feet and legs — but may also involve cranial nerves and autonomic pathways.

The condition can manifest in multiple forms:

Distal symmetric polyneuropathy (the most common)

Autonomic neuropathy (affecting heart rate, digestion, or bladder control)

Radiculoplexus neuropathies (causing localized weakness and pain)

Mononeuropathies (affecting individual nerves, such as the oculomotor nerve)

Epidemiology: A Growing Global Burden

More than 500 million people worldwide live with diabetes, and up to 50% may develop neuropathy during the disease course.

In type 1 diabetes, neuropathy affects around 10–35% after 25 years.

In type 2 diabetes, up to 30% of patients show evidence of nerve injury within the first five years of diagnosis.

Risk factors include poor glycemic control, duration of diabetes, age, obesity, and metabolic syndrome. Early detection and tight glucose management remain the strongest preventive measures.

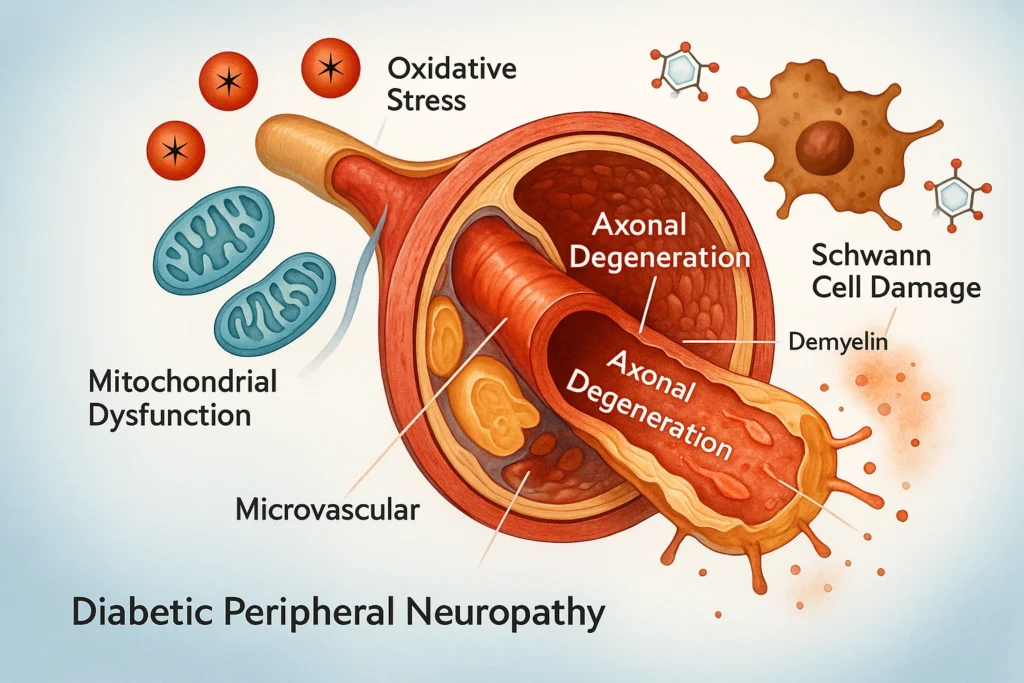

Pathophysiology: How Diabetes Damages the Nerves

The peripheral nervous system (PNS) is especially vulnerable because its sensory neurons lie outside the blood–brain barrier, making them directly exposed to circulating glucose and lipid toxicity.

Excess glucose leads to:

Mitochondrial dysfunction and reduced ATP energy production

Oxidative stress and reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulation

Axonal transport failure, impairing nerve repair and conduction

Degeneration of small unmyelinated fibers (C-fibers), causing early pain

Over time, both small and large fibers are affected, leading from pain and burning sensations to numbness and balance loss.

Clinical Presentations

1. Distal Symmetric Polyneuropathy

Starts in the toes and progresses upward (“stocking-glove pattern”).

Large-fiber involvement: Numbness, loss of vibration and proprioception, absent ankle reflexes.

Small-fiber involvement: Burning, tingling, and electric-shock sensations, often worse at night.

2. Autonomic Neuropathy

Affects involuntary functions:

Cardiovascular: Resting tachycardia, orthostatic hypotension.

Gastrointestinal: Constipation, gastroparesis, early satiety.

Genitourinary: Erectile dysfunction, bladder retention, reduced sexual arousal in women.

3. Radiculoplexus and Mononeuropathies

Lumbosacral radiculoplexus neuropathy causes severe asymmetric thigh pain and weakness.

Cranial mononeuropathies, such as oculomotor nerve palsy, cause acute eye movement deficits but often recover spontaneously.

4. Asymptomatic Neuropathy

Up to half of patients may have objective nerve damage without symptoms — a silent but dangerous stage that increases the risk of ulcers and amputations.

Diagnosis and Evaluation

Bedside Assessment

History: Onset, progression, pain type, and autonomic symptoms.

Examination: Sensation (pinprick, vibration with 128 Hz tuning fork), ankle reflexes, and gait.

Common Diagnostic Scales

| Scale | Use | Highlights |

|---|---|---|

| Michigan Neuropathy Screening Instrument (MNSI) | Simple screening | Questionnaire + foot exam |

| Toronto Clinical Neuropathy Score (TCSS) | Severity grading | Follows disease progression |

| Total Neuropathy Score (TNS) | Research standard | Includes NCS + sensory tests |

Electrodiagnostic and Laboratory Tests

Nerve conduction studies (NCS) and EMG to assess large-fiber damage.

Skin biopsy for small-fiber density when diagnosis is uncertain.

Autonomic testing (e.g., QSART, tilt table) if dysautonomia is suspected.

Lab work-up: Vitamin B12, renal, thyroid, autoimmune, and toxicology panels to rule out other causes.

Management of Diabetic Neuropathy

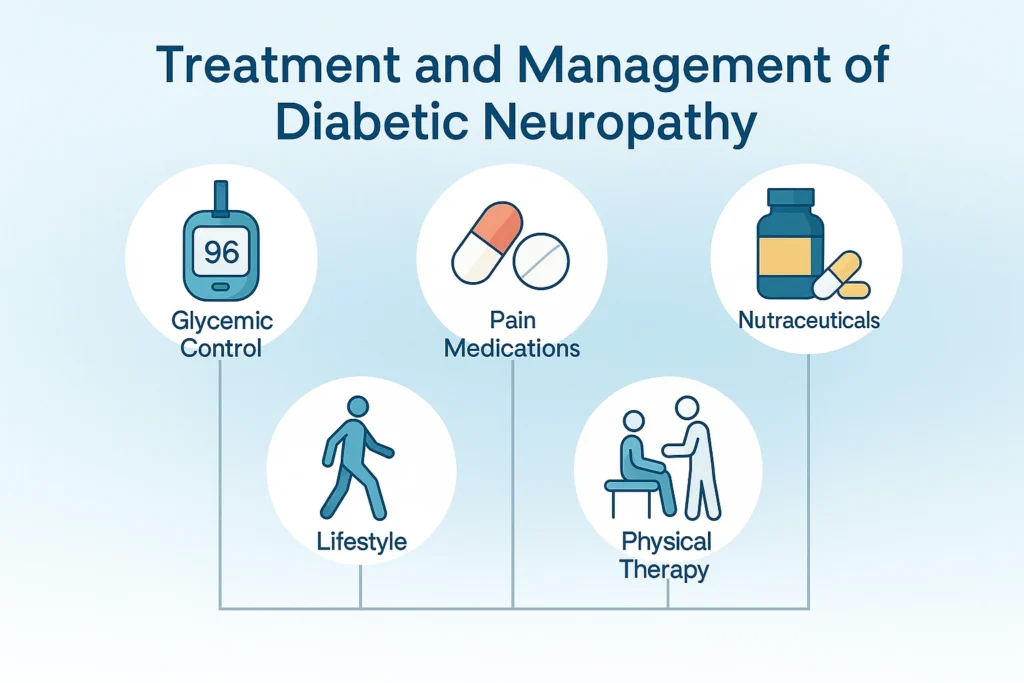

There is no single curative therapy, but a combination of metabolic control, pharmacologic, nutraceutical, and lifestyle interventions can significantly improve outcomes.

1. Glycemic Control

The cornerstone of prevention and progression delay.

Studies (DCCT, UKPDS) demonstrate that stable blood glucose markedly reduces neuropathy risk.

2. Pharmacologic Treatments

| Medication | Category | Key Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Duloxetine | SNRI | FDA-approved, effective for neuropathic pain |

| Pregabalin | Anticonvulsant | FDA-approved, improves sleep and QoL |

| Gabapentin | Anticonvulsant | Cost-effective alternative |

| Amitriptyline / Nortriptyline | Tricyclic antidepressants | Useful but limited by side effects |

| Topical Lidocaine | Local analgesic | For focal pain, 5% patch |

| Opioids (Tramadol, Tapentadol) | Avoid if possible | Risk of dependence, short-term use only |

3. Nutraceuticals and Supplements

Some evidence supports adjunctive nutraceuticals:

| Agent | Mechanism | Status |

|---|---|---|

| Alpha-lipoic acid (ALA) | Antioxidant, improves nerve conduction | Widely used, good safety profile |

| Benfotiamine (Vitamin B1) | Reduces oxidative stress | Promising in Europe |

| Acetyl-L-carnitine | Enhances mitochondrial function | Potential benefit |

| Vitamin D & E | Antioxidant support | Insufficient data but safe |

| Gamma-linolenic acid (PUFA) | Anti-inflammatory | Adjunctive use |

4. Non-Pharmacologic Approaches

Exercise: 150–300 min/week of moderate aerobic activity + strength training twice weekly improves balance and reduces pain.

Diet: Mediterranean-style or low-glycemic diet reduces insulin resistance.

Physical therapy: Essential for gait and proprioception.

Nerve stimulation (TENS, SCS, TMS): May relieve refractory neuropathic pain.

Behavioral interventions: Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and mindfulness can enhance pain coping and sleep quality.

Future Directions

Despite progress in understanding mitochondrial bioenergetics and axonal degeneration, no disease-modifying therapy yet exists. Future research must focus on:

Identifying biomarkers for early detection

Developing neuroprotective and regenerative agents

Evaluating combined pharmacologic + lifestyle interventions in long-term studies

Key Takeaways

Diabetic neuropathy affects 1 in 2 people with diabetes and remains a leading cause of disability.

Early detection and strict glucose control are vital to prevention.

Duloxetine and pregabalin remain first-line pharmacologic options.

Nutraceuticals like ALA and exercise programs offer promising adjunctive benefits.

Multidisciplinary management — neurologists, endocrinologists, physiotherapists, and dietitians — provides the best outcomes.

Resources & References

American Association of Neuromuscular & Electrodiagnostic Medicine (AANEM), 2025. Diabetic Neuropathies, Muscle & Nerve, 2025; 0:1–12.

American Diabetes Association (ADA), 2024. Standards of Care in Diabetes – Microvascular Complications and Foot Care.

Feldman EL et al. Diabetic Neuropathy, Nature Reviews Disease Primers, 2019.

Callaghan BC et al. Lancet Neurology, 2022.

Elafros MA et al. Continuum (2023): 1401–1417.