Abstract:

Trigeminal neuralgia (TN) is a severe, paroxysmal facial pain syndrome resulting from focal demyelination and neuronal hyperexcitability within the trigeminal system. This review synthesizes current knowledge on its pathophysiology, diagnostic framework, and evidence-based treatment strategies, offering clinicians a comprehensive update on this complex neuropathic pain disorder.

Introduction

Trigeminal neuralgia is one of the most excruciating pain syndromes encountered in clinical neurophysiology and neurology. Characterized by sudden, electric shock-like facial pain, TN often leads to misdiagnosis—frequently mistaken for dental pathology—resulting in unnecessary procedures and delayed therapy.

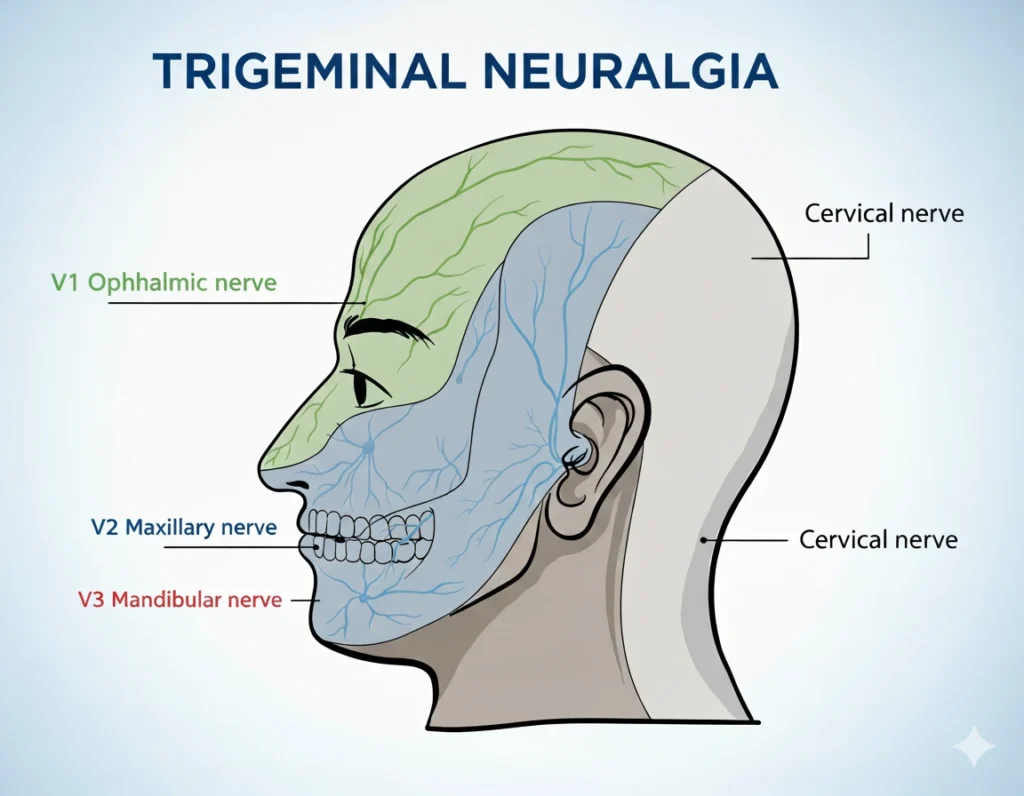

The disorder predominantly affects the maxillary (V2) and mandibular (V3) divisions of the trigeminal nerve, almost always unilaterally. Its annual incidence ranges from 4 to 27 per 100,000 people, with a peak in middle-aged and elderly women.

Clinically, TN presents as brief, recurrent paroxysms of severe pain, often triggered by trivial stimuli such as chewing, speaking, or cold air. Between attacks, a refractory period may occur, and approximately half of patients experience persistent background pain of lower intensity.

Pathophysiology: Demyelination and Hyperexcitability

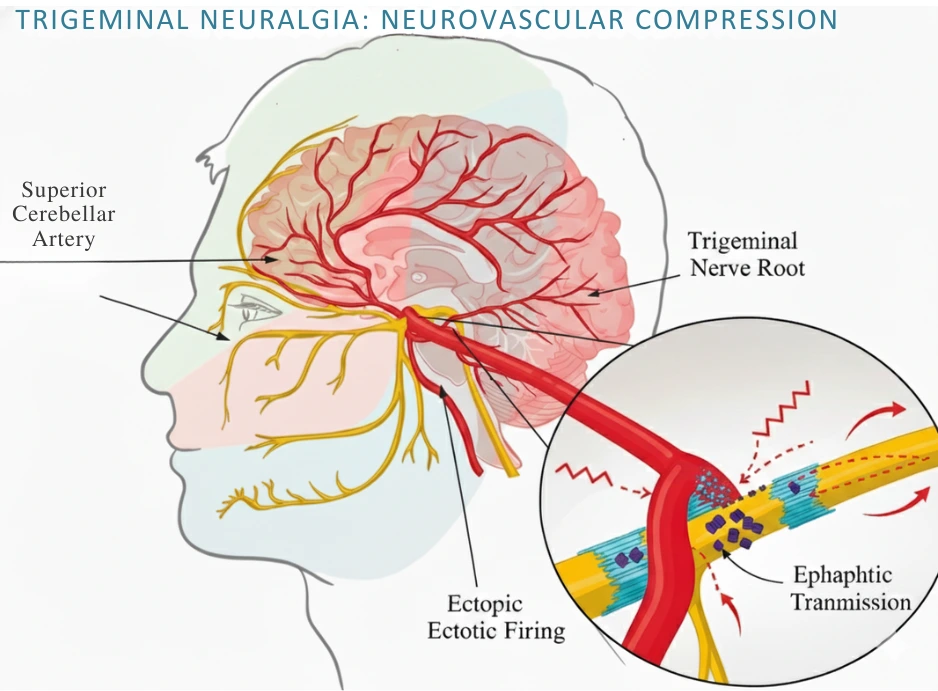

The hallmark lesion in trigeminal neuralgia is focal demyelination of the trigeminal nerve root. This structural alteration, typically induced by neurovascular compression, disrupts normal axonal insulation and leads to pathological excitability.

Two key electrophysiological phenomena explain the characteristic symptoms:

-

Ectopic Impulse Generation:

Demyelinated axons gain the ability to generate spontaneous impulses, creating pain signals even without external stimuli. Mechanical pulsations from adjacent arteries can amplify this activity. -

Ephaptic Transmission:

The loss of myelin allows “cross-talk” between neighboring axons—non-nociceptive impulses from tactile fibers can jump to pain fibers, producing paroxysmal pain.

Together, these mechanisms underpin the ignition hypothesis, which proposes that local demyelination and synaptic hyperexcitability generate self-reinforcing neural discharges, explaining both the intensity and the paroxysmal nature of TN pain.

Etiology and Contributing Factors

While focal demyelination is the unifying pathophysiological process, several etiologies can initiate it:

1. Neurovascular Compression (Classical TN)

In up to 90% of cases, a vascular loop (most often the superior cerebellar artery) compresses the trigeminal root entry zone. Only cases where compression causes morphological changes—such as indentation or distortion—are strongly associated with TN symptoms.

2. Demyelinating Disorders (Secondary TN)

Multiple sclerosis is the most common non-compressive cause. Demyelinating plaques in the pons involving the trigeminal root can produce identical pain attacks, often bilateral or associated with other neurological signs.

3. Structural and Rare Causes

Tumors (meningiomas, epidermoid cysts, schwannomas), vascular malformations, amyloidomas, or brainstem infarcts can all compress or damage trigeminal pathways. Rare familial cases suggest a minor genetic contribution.

Diagnostic Framework

The diagnosis of trigeminal neuralgia is primarily clinical. Key features include:

-

Sudden, unilateral, severe, brief facial pain (seconds to two minutes).

-

Electric shock-like or stabbing quality.

-

Triggered by innocuous stimuli in the affected dermatome.

Red Flags Suggesting Secondary TN

-

Sensory loss or numbness

-

Bilateral pain

-

Onset before 40 years

-

Poor response to carbamazepine

-

Ophthalmic (V1) involvement

-

Hearing loss or other cranial neuropathies

Differential Diagnoses

| Condition | Key Features |

|---|---|

| Painful post-traumatic trigeminal neuropathy | History of trauma or dental procedure, sensory deficit |

| SUNCT/SUNA | Short-lasting orbital pain with prominent autonomic symptoms |

| Odontogenic pain | Tooth-related, triggered by hot/cold stimuli |

| Glossopharyngeal neuralgia | Pain in throat or ear, triggered by swallowing |

| Persistent idiopathic facial pain | Dull, continuous pain without paroxysms |

Neuroimaging

High-resolution MRI of the brain is essential to rule out secondary causes (tumors, MS, vascular malformations). Neurovascular contact alone, however, does not confirm TN, as it is found in many asymptomatic individuals.

Management: Stepwise and Evidence-Based

Treatment follows a logical, escalating algorithm—beginning with medication and progressing to surgery if pain becomes refractory.

Pharmacological Therapy

First-line agents are sodium channel blockers that stabilize neuronal membranes and reduce ectopic firing.

| Drug | Class | Clinical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Carbamazepine | Sodium channel blocker | Most evidence-based; ~70% initial response. Side effects: drowsiness, hyponatremia, hepatic enzyme induction. |

| Oxcarbazepine | Sodium channel blocker | Similar efficacy, fewer drug interactions, preferred in older adults. |

| Lamotrigine | Sodium channel blocker | Used as add-on therapy; requires slow titration. |

| Baclofen | GABAb agonist | Adjunct or alternative, especially in MS-associated TN. |

Surgical Approaches

For medically refractory TN, surgery offers durable relief.

-

Microvascular Decompression (MVD):

The gold-standard procedure; aims to separate the compressing vessel from the trigeminal nerve with a Teflon implant. Provides long-term pain relief in ~80% of patients with low recurrence. -

Ablative Procedures:

(Radiofrequency thermocoagulation, glycerol rhizolysis, balloon compression, or stereotactic radiosurgery) selectively damage pain fibers to interrupt transmission. Used when MVD is contraindicated or refused.

The choice depends on the patient’s health status, imaging findings, and risk tolerance.

Conclusion and Future Directions

Trigeminal neuralgia remains a uniquely distressing neuropathic pain disorder rooted in focal demyelination and neuronal hyperexcitability. Despite excellent surgical outcomes and effective pharmacotherapy, significant gaps persist in predicting prognosis and preventing recurrence.

Future research must focus on objective biomarkers, advanced neuroimaging for better diagnostic accuracy, and novel treatments such as botulinum toxin injections and neuromodulation therapies.

For clinicians, early recognition, multidisciplinary management, and patient education remain key to reducing suffering and improving long-term outcomes.

References

-

Maarbjerg S, Gozalov A, Olesen J, Bendtsen L. Trigeminal neuralgia – diagnosis and treatment. Cephalalgia. 2017.

-

Zakrzewska JM, Linskey ME. Trigeminal neuralgia. BMJ. 2014.

-

Love S, Coakham HB. Trigeminal neuralgia: pathology and pathogenesis. Brain. 2001.

-

International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (ICHD-3).

-

American Academy of Neurology (AAN) Practice Parameters: Management of Trigeminal Neuralgia.

External resources: